Professor Travers Child: Guiding theories of change are needed for ESG initiatives to be effective

The increasingly widespread view of ESG as being a pragmatic, forward-thinking kind of business sense – beyond its moral and progressive characteristics – is a relatively new phenomenon. The shift in mindset from all manner of global organisations viewing it as “nice, but expensive to implement” to “nice, and expensive to ignore” is the culmination of innumerable trends in emerging technologies, shifting consumer preferences and advocacy levels, massive political upheaval and, of course, the looming threat of climate change.

However, the intention of “doing good” doesn’t always easily translate into “doing good well”. When it comes to ESG and wider activities related to enabling some measure of societal good, all manner of organisations, from government institutions to corporate entities, frequently fall into the trap of focusing too much on optics and too little on outcomes.

Given his background in development economics (and research focus on the effectiveness of foreign aid and government-funded development projects), we decided to sit down with CEIBS Associate Professor of Finance Travers Barclay Child to ask him about the pitfalls of poorly planned, poorly measured, and poorly implemented activities of this kind.

Looking beyond the numbers – Researching the efficacy of foreign aid

Foreign aid is a tricky business to get right, even when the effort is being made with the best of intentions. Too often, the assumption is made by governments, NGOs and private enterprises that throwing money at a problem will automatically begin to make a dent in it.

“When I first began my research in 2007, very few people were really trying to carefully measure whether reconstruction development actually helps the target country or community,” Professor Child explains. “Intuitively it just seems as though it would help, or at least do no harm. You're spending a bunch of money on positive things, you’re building roads, schools, and hospitals; surely it must be leading to positive outcomes, right? But this should not be taken for granted, so I challenged that notion through my research.”

This simple idea of testing the efficacy and inefficacy of foreign aid projects led Prof. Child to conduct a quantitative assessment of around 33,000 foreign aid and development projects in Afghanistan, supported by face-to-face interviews and his actual fieldwork in Kabul.

Condensing his painstaking research into a simple overview, Prof. Child then explained how it could be possible for implementers of these projects to forge ahead with the best of intentions but without a guiding theory regarding how the desired positive outcomes may be achieved in reality.

How foreign aid works… and how it doesn’t

In the recent history of conflict-affected or post-conflict areas in the Middle East, the US Government and its allies have demonstrated a constant and pressing desire to demonstrate ‘progress’; progress not just in terms of military successes and subsequent security and stability, but progress in winning ‘hearts and minds’. To oversimplify an inherently complex counter-insurgency strategy, winning hearts and minds means providing the local population with various improvements to their daily living standards (e.g., better education, healthcare, access to utilities, job opportunities, etc.). In return, the local population are expected to slowly become more accepting of foreign military presence and its goals of regime change.

This isn’t purely transactional politics at play, either. Such development efforts may also be motivated by a genuine desire of individuals, companies, NGOs, and governments to build better futures for people in countries ravaged by war. However, the sad reality is that delivering effective foreign aid and development is not as simple as turning on a money tap and watching the goodwill flow.

“Firstly, you have to start from the premise that it’s not easy to anticipate the impact your project will have, it’s hard to avoid its unintended consequences, and it’s even harder still to accurately measure its outcomes,” says Prof. Child.

“When you factor in miscommunication between stakeholders, shifting or conflicting priorities, and the presence of rampant corruption, even the most well-intended and highly resourced projects can fail or achieve negligible effects. Worse still, projects can actually yield negative outcomes for their intended recipients,” he continued.

As a concrete example, Prof. Child pointed out how a lack of foresight and planning can easily lead to unintended consequences that destabilise a project from the outset:

“My research enables a comparison of the relative outcomes of foreign-led education and healthcare projects in Afghanistan. Healthcare projects can be more straightforward to yield positive outcomes – you strengthen medical infrastructure and services, health benefits are realised, and that’s a relatively non-controversial advantage for society. With education projects, there are much more complex factors at play. Foreigners can be perceived as pushing a progressive educational agenda onto a deeply conservative population wary of foreign soldiers. Without a heavy dose of cultural sensitivity and community engagement, the chance of projects backfiring and alienating local populations can be considerable,” he says.

Bringing insights from the wider world into the classroom

Despite this gloomy assessment of past performance in Afghanistan and other conflict areas, Professor Child remains confident that the lessons learned in such regions can be applied to good effect. From foreign aid efforts to the work of charities and other NGOs, and even the ESG-based developmental ambitions of private companies, the importance of prior planning and preparatory groundwork cannot be overstated when it comes to driving better outcomes.

To this end, having made the jump from academic research to teaching (while still engaging in top-level research), Prof. Child is excited to bring what he has learned in the field to the classroom as the teacher of the Business Ethics core course for CEIBS’ MBA programme.

“Research and teaching both come with their own kind of influence,” he says. “I enjoy conveying these ideas to students, so that hopefully they can take the implications back to their companies. Then, when it comes to planning their next big ESG-related project, maybe they will approach it with more careful thought around project objectives, a guiding theory of change, and a calculated allocation of resources.”

According to Prof. Child, the cardinal sin when embarking on an ESG project is rushing into it with a greater emphasis on how it makes the organisation look, rather than what it can tangibly achieve.

Future focused – AI may bring clarity to the table

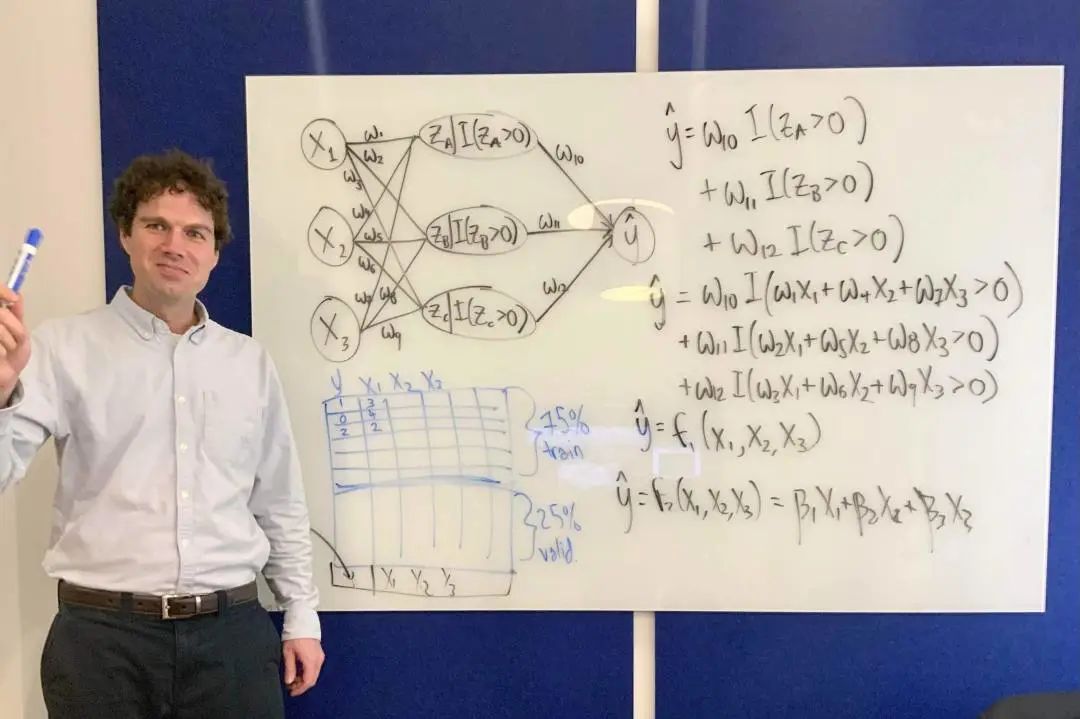

Alongside the CEIBS MBA Business Ethics course, Professor Child also teaches an AI and Machine Learning class, another key focus area of his current research.

Professor Child passionately believes that accurate data analysis is the best weapon for understanding the impact of foreign aid, and that the same goes for all manner of ESG-inspired initiatives. With its analytical powers only just being tapped into, AI may prove to be key to unlocking insights that lead to consistently better outcomes on such projects. While better tools often enable better outcomes, there’s clearly no substitute for the business fundamentals of proper planning, clear objective setting, intelligent design, and open collaboration with all stakeholders to ensure that the outcome isn’t left to chance. We look forward to seeing where Professor Child’s research leads him, and his students, next.