How can we keep things on track during a resurgent pandemic?

New outbreaks of COVID-19 have surged across China, plunging cities into another round of massive lockdowns, most recently in Shanghai. As life and work seem to be slipping out of control, it is easy to feel gripped by a renewed sense of anxiety as we struggle to adapt to changes that are happening all too quickly.

When life is derailed and powerlessness takes hold, what can we do to stay on our feet? CEIBS Global EMBA 2001 alumna Linda Zhang shares her opinions and coping plans regarding the prevailing bewilderment that many of us are currently facing.

Linda Zhang

Independent Executive Coach and Leadership Consultant

Master Certified Coach (MCC), International Coaching Federation (ICF)

CEIBS Global EMBA 2001 Alumna

Ph.D. in Organisation Development and Change, Fielding Graduate University

Disorder Triggered by Epidemic

The COVID-19 epidemic is the third epidemic I have been through. The first was the hepatitis outbreak in 1988, when I was still in university (I can still remember the pungent smell of detergent that filled the air in our dormitory). The second was the SARS epidemic in 2003, when I was in Shenzhen, pursuing my studies at CEIBS and shuttling every month between Shenzhen and Shanghai. I was once detained in Shanghai because of SARS. However, due to their short duration, these two epidemics did not wreak that much havoc upon people’s lives.

However, looking back on this latest round of COVID-19 outbreaks, it has already been a mental and psychological rollercoaster. When the pandemic initially broke out in 2020, there was a feeling that everything was in freefall. Now, we are full of expectations that things will finally fall into place, just to see them plummeting into disorder again.

After two years, the pandemic still has not ended. On the contrary, it continues to rage again across the country, forcing provinces, cities and people to isolate and even adopt full lockdowns that have caused huge disruption while carrying a major psychological impact on individuals. As long as this remains the case, mass anxiety will persist, which is itself a major cause of continuing disorders, for individuals and for society at large.

Given that many of our alumni are sandwiched between their parents and their kids, how should they pass these special days with three generations under the same roof? How can employees, who are denied face-to-face communications, remain united in their teamwork? These are all critical issues that will increase in importance as the pandemic situation deteriorates, and they may be much more consuming than we could ever imagine.

Here, I would like to cite the theory of entropy increase, which describes a spontaneous evolutionary process from order to disorder or chaos. Unless we invest more in curbing this natural tendency and create more order, we will keep losing control and subject ourselves more and more to an overall sense of powerlessness. Furthermore, since any meaningful defence against the pandemic is beyond the capacity of any single individual or group, this sense of powerlessness will be even stronger.

Anxiety and Depression amidst an Existential Threat

Two kinds of sentiments – anxiety and depression – are typical during such complicated scenarios.

The first, anxiety, comes more from worry and fear concerning future uncertainties. Even those who are normally in good health can be vulnerable to anxiety if they are suddenly exposed to too much duty and pressure, without a suitable outlet.

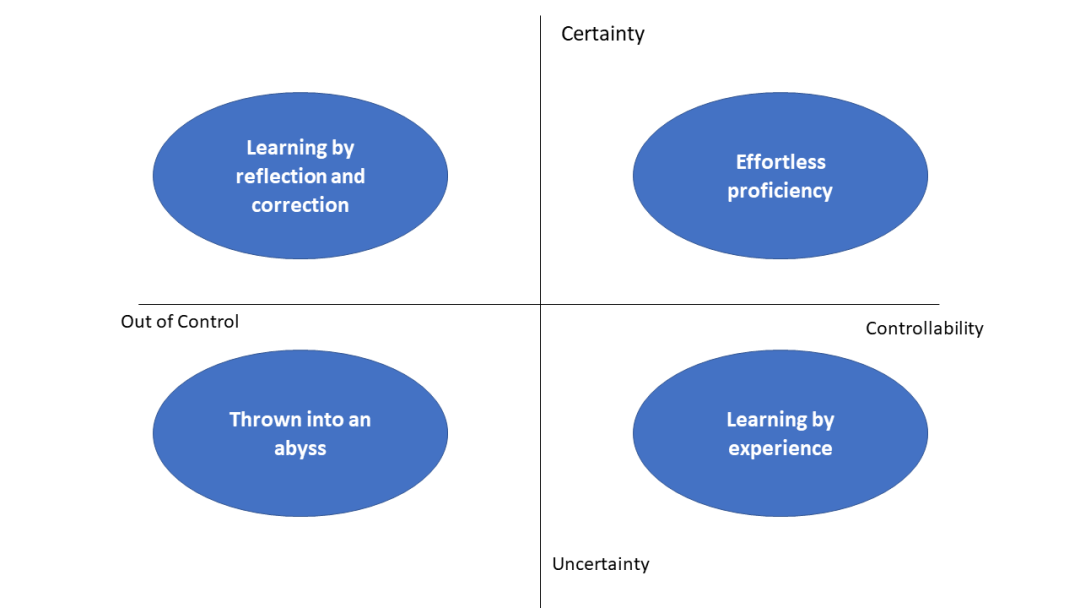

Uncertainty means changefulness. Both changefulness and uncontrollability have their counterparts, constancy and controllability. Based on these two sets of dichotomies, we could draw a two-dimensional map with four quadrants labelled certainty-controllables, certainty-uncontrollables, uncertainty-controllables and uncertainty-uncontrollables. Throughout our lives, we experience scenarios of the first three quadrants that are characterised by an increasing level of difficulty from one to the next. Such experiences help extend our ‘comfort zones’ and enhance our ability to solve problems as we learn more skills and develop good habits through them.

However, when we are in the uncertainty-uncontrollables quadrant, we can feel as if we’ve been thrown into an abyss, one that devours our once firmly-grounded sense of self-worth.

The reason why the current pandemic situation could give rise to such a sense that things are out of control is that no one is sure when it will come to an end, and when our dislocated lives can be brought back on track.

At its very root, such anxiety is an existential crisis which may be easy to cope with for optimists. Pessimists, however, may be susceptible to depression in this kind of situation. This is especially true for those who already bear huge pressures in their daily lives, where lockdown and isolation may add to their psychological stress. These people should be given special care in such cases.

Over-confidence may complicate the pressure of executives

For corporate managers, the situation is more complicated. For example, the targets they set for their teams at the beginning of the year may be set back because of new outbreaks, and some companies may even be threatened by bankruptcy. In such difficult cases, layoffs, and subsequently compensations, may be inevitable, which are all hard nuts to crack.

The epidemic provides a litmus test to business leaders, and particularly the change-handling abilities of companies as well as the solidarity, perseverance and innovation capabilities of their teams. If companies are able to deal with important matters with high efficiency and agility, and provide quick, short-term wins for the time being, they can earn more trust from their employees. Otherwise, they might be subjected to even more cataclysmic scenarios.

Another key consideration is that many corporate executives seldom show their vulnerability to others. Corporate executives are a highly confident group, who continually tell themselves, “I’m the best.” Even during times of great difficulty, they believe they can hold out. However, when they go overboard in exercising their confidence and related strengths, this may land them in a disadvantaged state. The idea of “being omnipotent” is an illusion in itself.

Accordingly, we need to make use of the support systems around us to reduce the pressure we face. For example, for those of us working in MNCs, our partners and peers at headquarters may be less informed about current market conditions in China, and we need to reassure them that our China-based team is working together against all odds and is going all out to protect the company’s bottom lines. By keeping our headquarters updated, we can reduce their need to maintain a helicopter type of control of regional markets and reduce the exhaustion they experience as a result of uncertainty.

One of the decisive factors that enable companies to tide themselves over is the organisational culture that they have developed in normal times, rather than any “superman” within it. A company’s organisational culture is an important cornerstone for its sustainable development and if it is one that embraces openness, cooperation and innovation, it can give it the vitality and resilience it needs to help its staff through difficult times.

Measures for Regaining Control

How can we reduce the negative feelings associated with everything being in a state of disorder?

Here, I would like to cite the theory of entropy again, which suggests a powerful way to alleviate such feelings by reducing one’s entropy in life by means such as increasing orderliness and controllability, growth mind-sets, and using some measures for regaining control.

For example, we may need to focus on the determinant factors in things and let go of the peripherals. In Tao Te Ching, Lao Tzu said that, “To have little is to possess. To have plenty is to be perplexed.” We need to remember this and stay focused on the few things that really matters.

To offer a more specific work-related example, we need to focus on key items and affect change by mobilising collective wisdom or by minimising tasks that are highly energy-consuming. For example, as senior executives, we often find our schedules packed with meetings and conferences. By managing to finish 1-hour meetings within 45 minutes, for example, we could save the rest 15 minutes for leisure, or a simple break, which can be very helpful for reducing both mental and psychological pressure.

The second is to keep a more optimistic and open mind-set. While I was preparing my Ph.D. dissertation, I found that many mid-life executives have experienced post-traumatic growth, which is mostly due to their openness and optimism.

Optimism enables us to see things in a more rational manner. For example, during this round of the outbreak, we can see that its severity is being lessened despite its more rapid speed of expansion, indicating that it is beginning to subside. This should give us hope, make us feel more positive and more willing to join hands with others in combating the pandemic.

We have discovered that those who have a sanguine and open attitude in life are more apt to find resources and establish connections with others, thereby planning their work and life in a more orderly manner.

At this stage, there are still a number of external factors that dampen optimism. In the past few decades, sustained economic growth in China has accustomed us to believing that things will always be better in the future. This, however, is just wishful thinking. Throughout our lives, we might realise some goals through our individual efforts, but that does not necessarily mean that we can make everything better in life. For example, the onset of old age and the loss of one’s parents are inevitable. A brain tumour patient I have interviewed said that after he became sick, he discovered that his destiny was something beyond his control. However, though he could not decide whether it would rain tomorrow, he could choose to protect himself from getting wet.

The pandemic has also taught us that we are not living in a fairy-tale. If we are not prepared to face all kinds of ups and downs in life, then such sentiments are just signs that we have yet to see enough of life. Today, we need to have the mentality that even “if things are not better tomorrow, I could still remain optimistic, positive and open-minded towards everything that life has in store for me.”

Changing Your Mind-set and Showing Your Vulnerability

Changes in mind-set cover all aspects of living – not only work, but also dealing with family challenges as well.

When working from home, we are unable to get together with our colleagues. Under such circumstances, what should we do to maintain team solidarity? There could be various possibilities, from organising new types of team-building activities online to maintaining cohesion under quarantine.

In this very special context, how should we maintain and improve our level of customer care? As transactional relationships recede and genuine connections assume more importance, how should we keep them alive?

In terms of family relations, we need to have a carefree family ambience since we are staying with our families all day long instead of being separated during the daytime. Parents need to learn to tell jokes and do exercise lessons with their kids, or other innovative ways to create happiness and joy. Here, I would like to recommend The Asada Family, a Japanese movie featuring the life of a family of four, which could provide some inspiration.

The key to establishing new mind-sets is to grow from past experiences and dare to take new actions to make the most of new circumstances, to do things to make everyone feel safe and protected and feel that they are not alone.

Be it the pandemic or other setbacks in life, these situations give us new chances for understanding and growing.

Faced with uncertainty and uncontrollability as well as the subsequent consternation they bring, we need to accept reality, to accept both ourselves and others, allowing expressions of weakness both with others and for ourselves.

When in quarantine, a manager also needs to assume the role of a captain, and provide more positive feedback and incentives to let disoriented team members know their direction.

Meanwhile, as individuals, it is important to accept our own feelings of vulnerability and allow such feelings to be expressed. One effective means is to write diaries or journals, taking several minutes every day to record our daily lives to quiet ourselves down mentally.

As for specific lifestyles, another important element is to pay more attention to our diet and exercise. Many people, because of work pressure, tend to resort to indulgence as an outlet. However, compared with binging on food or mobile surfing, developing small hobbies can be more helpful to avoid secondary health hazards. ‘Information deluge’ nowadays is also another source of exhaustion, and being obsessed with epidemic-related information can only lead to more tension.

Regarding exercise, many tend to think that they need to do it in suitable places. A friend of mine used to be quarantined quite often because of frequent traveling, and he bought himself a stationary bicycle to use in his hotel room. Therefore, what is truly important is to develop an awareness of the need to exercise, and make it part of our daily activities.

Amongst the midlife executives that I have interviewed, many have suffered from health problems because of work pressure, and unhealthy lifestyles often precipitate chronic diseases becoming acute ones, even to the extent of becoming life-threatening.

When we are unable to change the environment around us, we can still find the means to manage our lives and health, thus bringing life from disorder back to order and reversing entropy.

Writer:

Linda Zhang

Editor:

Tom Murray, Effy He and Michael Thede